Roopa Vasudevan is a media artist, computer programmer and researcher, currently based in Philadelphia. Her work examines social and technological defaults; interrogates rules, conventions and protocols that we often ignore or take for granted; and centers humanity and community in explorations of technology’s impacts on society. Through a varied creative toolkit that includes data collection practices, systems design, web development, and remix, she seeks to emphasize personal and human experiences, often on an individual or local level, in a time of Big Data and surveillance capitalism. Vasudevan’s artwork has been exhibited and featured by media outlets internationally, and she has participated in residencies, taught workshops and classes, and spoken about her practice around the world. She is a member artist at Vox Populi, a 30+ year old collectively run arts space in Philadelphia; a member of the Art & Code track at NEW INC, the art and technology incubator at the New Museum (New York, NY); and a two-time nominee for the Knight Foundation’s Arts + Tech Fellowship (administered by United States Artists). Vasudevan is also currently a doctoral candidate at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania, where she is researching the complex and involved relationships between new media artists and the tech industry.

Refusing Co-optation, Acting on Futurity: New Media Art, Social Practice & Creative Resistance

In the summer of 2020, amid the COVID-19 pandemic and worldwide uprisings for racial justice, I began leading a series of virtual workshops with fellow artists. Stemming from a profound personal discomfort with the ways that digital artists are primed to respond to surveillance and tech inequality in a siloed, individualistic manner, the workshops were designed to bring together practitioners in small groups to stimulate conversation about the promises and pitfalls of what is often called “creative resistance”: the use of art to subvert, refuse or push back against oppressive or ethically suspect power structures.

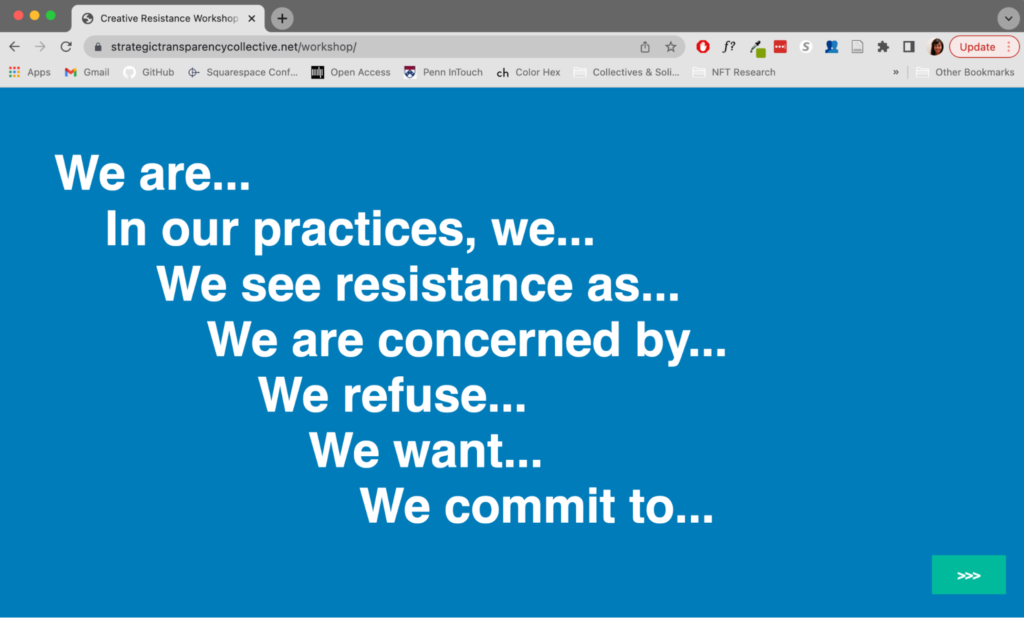

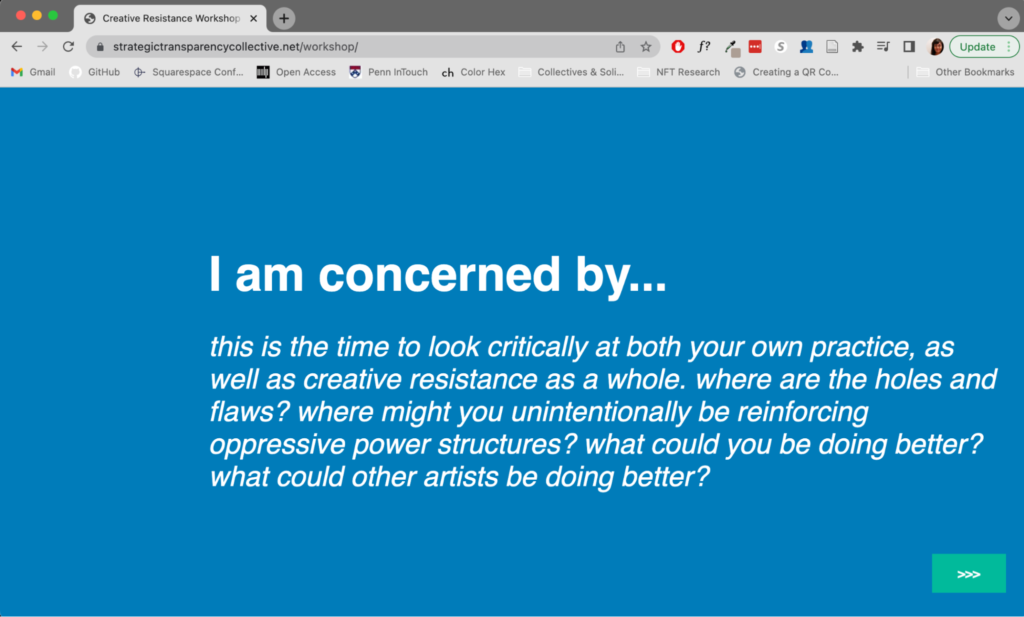

Through a format that combines personal free-writing exercises, intimate group discussion, and collective artmaking through the collaborative drafting of “manifestos for creative resistance”, the workshops were able to spark a process of values alignment among participants, and pointed to a dire need for collective conversation about shared goals, common decision-making processes, and mutually felt trepidation or anxiety related to relationships with industry and power. The sessions draw from a tradition of social practice artwork that engages community as a creative method (Bourriaud, 2002; Helguera, 2011; Bishop, 2012), along with multimodal approaches to research that position creative work as knowledge production in its own right (Jackson, 2014; Cox, 2015; Kondo, 2018).

Over the last two years, the workshops have developed from an experimental creative project into one of the core research strategies within my dissertation work. I have continued to lead workshops in a variety of contexts—to date, over 50 tech-engaged artists and/or practitioners have participated in one of these sessions. I have expanded the project into a decentralized network of practitioners who align to core values of self-reflexivity and criticality when it comes to personal and creative engagement with technology; I have also been able to re-envision the workshop prompts and formats in public art and Net art-based contexts.

Taken as a whole, the use of this method provides insight into the personal and systemic barriers that tech-based artists face when making work that attempts to confront and question embedded power structures in the field, while also providing a means of collaboratively imagining what would be necessary to align artists’ personal ethical beliefs with their everyday practices.